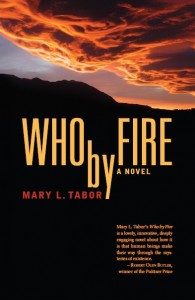

Outer Banks Publishing Group author Mary L. Tabor’s literary novel, Who by Fire, won the Notable Indie award for best books in 2013 by online magazine Shelf Unbound.

Shelf Unbound’s second annual writing competition had over 1,000 entries with 100 titles chosen as winners, according to Shelf Unbound’s publisher, Margaret Brown.

Mary’s book was featured in the December-January 2014 special edition of Shelf Unbound magazine (Page 35).

“Thanks to the Internet, artists can be discovered by a global audience-and in some cases even be funded by philanthropic strangers. The challenge, of course, is the discovery part-how do the indie artist and the indie audience find each other? That’s what this special issue of Shelf Unbound-honoring the winner, finalists, and notable entries in our second writing competition for best indie book-is all about,” wrote Ms. Brown.

Congratulations to Mary for her notable achievement!

Book reviews with GIFs, those tiny videos that play over and over, are rather controversial among the old guard of book reviewers. Read Laura Miller’s insightful and informative piece. Start with the excerpt below.

“The GIFs and images used in the two reviews are, like the vast majority of visual elements cropping up in reviews and other critical discussions online, reaction GIFs: looped clips taken from commercially produced film and television, often featuring popular actors such as Emma Stone or Jennifer Lawrence rolling their eyes, gaping in astonishment, jumping with glee, shrugging their shoulders. They serve to underline the reviewer’s point, rather than to make it, and they can come across as exaggerated and sarcastic, even bratty. But so what? It’s not as if traditionally published professional book reviews haven’t been equally harsh at times, and in this case, the reviews are highly attuned to their intended audience with its densely networked language of cultural references. Besides, as longtime Goodreads member Ceridwen (who doesn’t use images or GIFs herself) explained to me in an email, ‘These reviews often use the very same critical tools found in professional reviews — parsing of character and tone, close reading, comparison with other works or larger cultural positioning — [but] there’s no fiction of critical distance, and the emotional reaction is as important as the aesthetic one.'” >more

By MICHAEL JOHNSON

Novels about love affairs outside of marriage are a genre unto themselves and I try my best to avoid them. John Updike made a career of these stories anyway, so what’s left to say? Yet once in a while a new writer emerges with such sharp sensibilities, such descriptive powers, and such a rich story that I am forced to reconsider.

Mary L. Tabor is such a writer, and her new book, “Who By Fire” (Outer Banks, $17.95), launched a few weeks ago to a full house in a Washington, D.C. bookshop, kept me turning pages to enjoy the careful prose, the fascinating digressions and most of all the unspooling of the story.

To my mind, the story is the fire in the relationships. The ice is Ms. Tabor’s masterly control of the complex plot. The reader begins to suspect what is to come as hints are dropped along the path toward the climax. This book is hard to put down.

“Who By Fire” is a near-surgical dissection of the turmoil and pleasures that straying couples experience – and the effect on the betrayed.

Ms. Tabor takes the time to develop characters so that you care about what they are going through. She finally kills off Lena, the woman who succumbed to her lover’s charms, and she does it abruptly after setting the scene: “And then she died.”

Mary Tabor is a writer who likes to say it is never too late. She started publishing her prose at age 60 and already has to her credit a frank memoir of her life and marriage entitled “(Re)Making Love: A Memoir.” Her best short stories are collected in “The Woman Who Never Cooked.”

Mary Tabor is a writer who likes to say it is never too late. She started publishing her prose at age 60 and already has to her credit a frank memoir of her life and marriage entitled “(Re)Making Love: A Memoir.” Her best short stories are collected in “The Woman Who Never Cooked.”

She takes stunning risks in her new novel, the most impressive being her decision to write from the perspective of Lena’s husband, Robert, the man who suffers as his emotions of widowhood and awareness of his dead wife’s affair mingle in his thoughts.

Jay McInerney tried the gender-swap in “The Story of My Life” but he never let you forget he was trying to sound like a girl. Ms. Tabor glides into the male perspective effortlessly and stays there.

As the narrator “Robert” reconstructs the story of his life, Ms. Tabor makes him recall what he had failed to see before his wife’s death:

“If I’d seen them on the street, I’d have known because they would have done the sorts of things that reveal: They would have passed between them a bottle of water, their hips would touch, as if by accident, when they walked; they wouldn’t touch with their hands the way safe lovers do, but an observant eye could catch both the intimacy and the caution—and know. It was when she was dying that I knew. It was the way he touched her head before he left her bedside. What I thought was an obligatory visit from a colleague changed with one gesture.”

I was propelled through this book most of all by the taut language, the dialogue and the perfect sentences, honed in the author’s years as a teacher of creative writing at George Washington University, Ohio State and University of Missouri, among others. From the outset, you are in the thrall of a confident storyteller.

Her digressions take the reader into worlds she clearly knows — the detail of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the art world, the finer points of classical music, quantum physics and the business of psychology. She has her psychologist character Evan say at one point:

“I’m beginning to think I give more comfort than cure. Not such a bad thing but not what I expected. I feel like an old broom—cleaning up, moving around the messes in people’s heads, never sure if that’s all I’m doing.”

She will throw odd words at you and expect you to understand. The apple trees are espaliered. The plants are pleached.

I was drawn into the suspense when the lovers realize that the betrayed wife is returning home early. With cinematic realism, the lovers find themselves about to be discovered when they hear the key in the lock:

“A familiar sound, merely a click, but they thought, almost as if their minds were one, that they heard the separate mechanisms of the lock moving, tumbling like thunder.”

This reader quickly turned the page to watch them awkwardly lie their way out of trouble.

Mary L. Tabor tells me she is at work on a new novel. Somehow she finds time to do a weekly internet interview about writing, broadcast on Rarebirdradio.

It is never too late, as she would be the first to tell you.