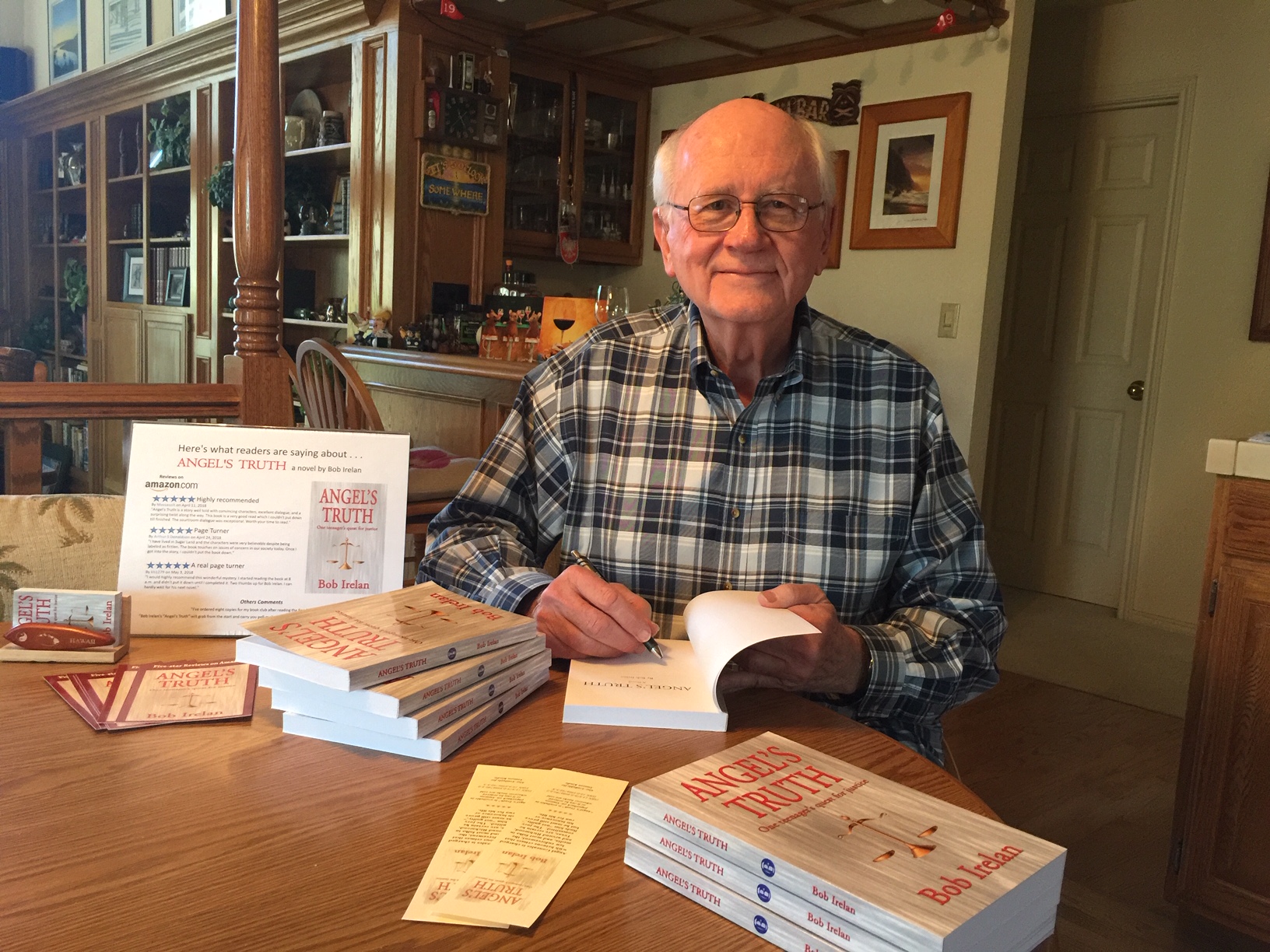

By Bob Irelan, Outer Banks Publishing Group author of Angel’s Truth

Talking to book clubs about writing and about the book you’ve written is an effective but underutilized marketing tool.

The advantages include:

Start off by telling your audience that “everyone has a story to tell,” and encourage them to tell theirs. It need not be a novel. Maybe it is a memoir, a collection of recollections and experiences that were personally important and may be of interest or guidance to others. Maybe it is a chronological narrative; maybe just a collection of anecdotes.

Start off by telling your audience that “everyone has a story to tell,” and encourage them to tell theirs. It need not be a novel. Maybe it is a memoir, a collection of recollections and experiences that were personally important and may be of interest or guidance to others. Maybe it is a chronological narrative; maybe just a collection of anecdotes.

Then talk about what motivates you to write, what you learn in the process, what ups and downs you experience, and the sense of accomplishment you feel when you finish the concluding sentence.

Comment on how the publishing business has changed . . . about how it has become more “author friendly.”

Having done all this, it’s time to read a key passage or two from your book.

Most important — leave plenty of time for questions. You will get them and they will provide insight into how people read and whether you succeeded in delivering your message.

Bottom line: You will enjoy the small group experience, your visibility as an author will be enhanced, and you will sell books.

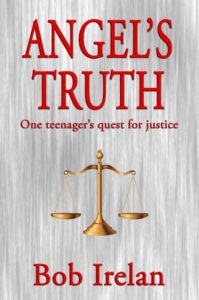

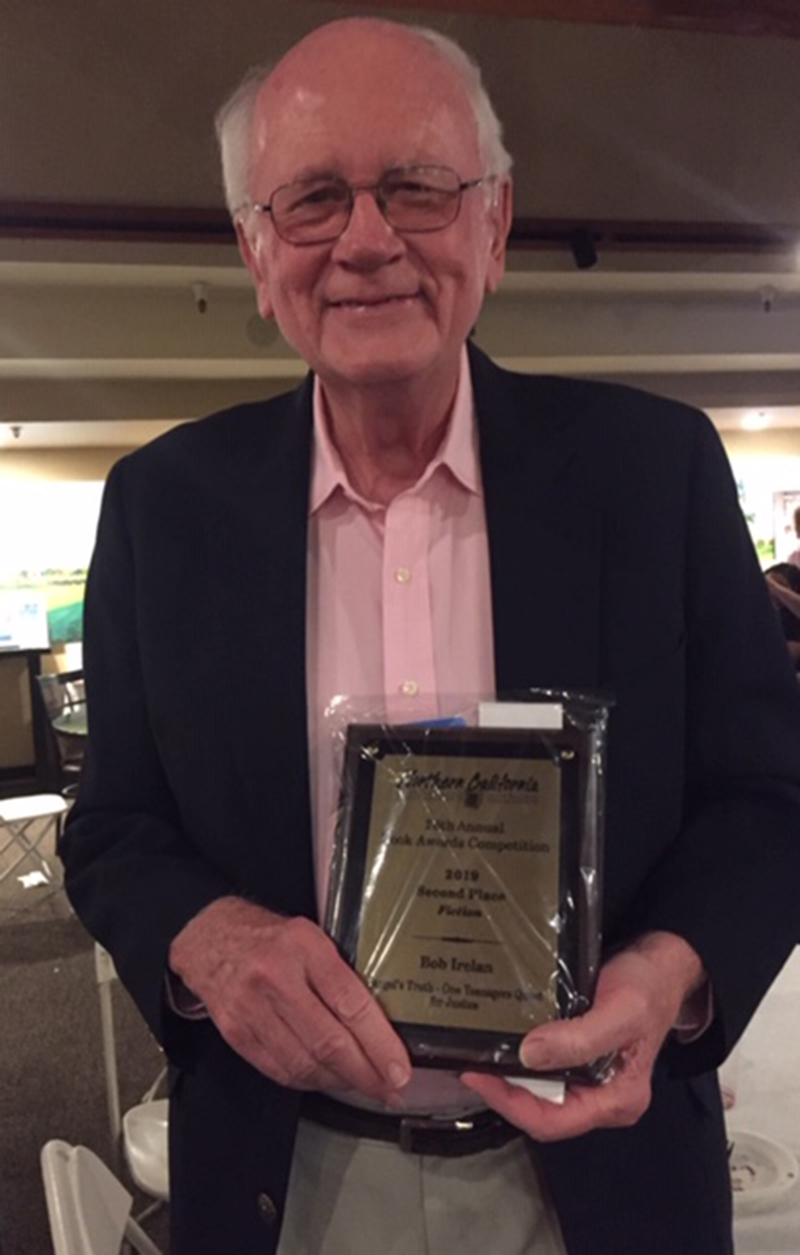

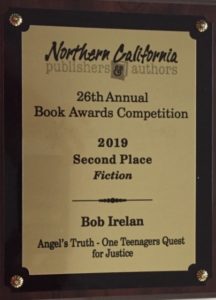

Outer Banks Publishing Group Author Bob Irelan recently won second place in the Northern California Publishers and Authors (NCPA) 25th annual book awards contest for his first novel, Angel’s Truth.

NCPA is an association of authors, indie publishers, and small presses based in Sacramento, CA with the goal to educate and encourage our members. The association is a regional affiliate of the Independent Book Publishers Association (IBPA).

NCPA is an association of authors, indie publishers, and small presses based in Sacramento, CA with the goal to educate and encourage our members. The association is a regional affiliate of the Independent Book Publishers Association (IBPA).

The contest is open to members and nonmembers alike. Books are evaluated in a variety of categories and are awarded based not only on relative rank to the other entries, but on intrinsic quality standards. Each book is read by three judges, and the judges gather for face-to-face discussion of their decisions.

Visit www.norcalpa.org for more information about the association.

Read what inspired Bob to write Angel’s Truth and how it is extraordinarily relevant today.

______________________

______________________

Order your copy at the publisher’s special discount of $11.99 – Save $4

USE THIS CODE – DISCOUNT40 – TO GET 40% OFF WHEN YOU CHECK OUT on your first purchase.

List Price:$15.995.5″ x 8.5″(13.97 x 21.59 cm)

Black & White Bleed on White paper

272 pagesOuter Banks Publishing Group

ISBN-13:978-0990679080

ISBN-10:099067908X

BISAC:Fiction / Crime

Angel Gonzales is charged with heinous crimes that law enforcement, the media, and most folks in Richmond, Texas, and surrounding communities are certain he committed.

The crimes and trial dwarf anything that has happened in that part of the Lone Star state in anyone’s memory.

When, against all odds, the jury renders “not guilty” verdicts, shock escalates to anger.

In the minds of many, justice has failed, and a brutal criminal is being set free. For Angel and his court-appointed public defender, Marty Booker, being judged “not guilty” isn’t enough.

Together and with help from an unanticipated source, they attempt to prove Angel’s innocence.

In the process, they butt up against prejudice, deceit, and a sheriff and district attorney who put politics, ambition, expedience, and arrogance above responsibility to do their jobs.

It’s a story of horror, hatred, belief, and persistence – a story of a Mexican-American teenager who nearly loses his life on the way to becoming a man.

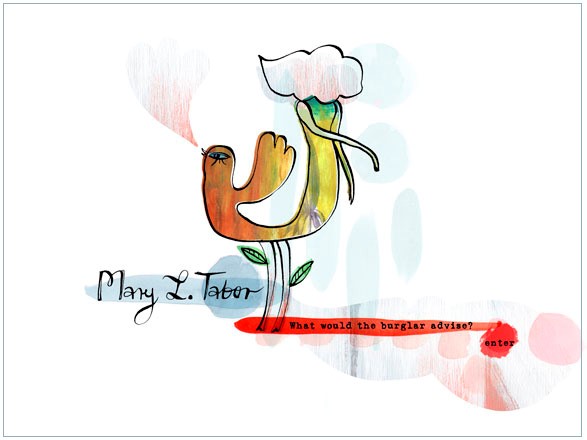

By Mary L. Tabor

Outer Banks Publishing Group author

How does autobiography work in fiction?

Subtitle: Why my collection of short stories The Woman Who Never Cooked might in some sense be called non-fiction. Here’s the probing answer to the difficult question, Where is the TRUTH? (*asterisks refer to footnotes at the end of this essay).

You know the line: Truth is stranger than fiction? I have a twist on that. I’ve learned through the writing of three books and a fourth in process* as I write this essay that the fictional account of my stories have greater emotional truth and intellectual significance than the factual ones.

Mary L. Tabor

As memoir has increased in popularity** both in books and movies—“A True Story” being the familiar movie tag—I’ve continued to argue that fiction, written close to the bone, will likely provide the reader with a deeper look into the life and soul of the writer, but more important, the reader if the story is worth your time.

Think first of this question, one that I pose to myself for purposes of this essay: Do you think self-revelation is part of the process of writing?

My answer: Any serious writer who denies it, lies.

Reality Hunger by David Shields

I agree with David Shields who argues in favor of self-revelation and to a large extent against the novel that is not self-revelatory. He does so in Reality Hunger through a series of quotes, occasionally his own—unabashedly without full attribution (but that’s another story) using only the name of the writer. Here’s John Berger, “Authenticity comes from a single faithfulness: that to the ambiguity of experience.” And later, the late David Foster Wallace, “I don’t know what it’s like inside you and you don’t know what it’s like inside me. A great book allows me to leap over that wall: in a deep, significant conversation with another consciousness, I feel human and unalone.” ***

A serious writer can’t help but reveal even as the lie of fiction operates.

Lee K. Abbott, a writer and teacher I know and admire, has put the issue succinctly this way: “All stories are true stories, especially the artful lies we invent to satisfy the wishful thinker in us, for they present to us, in disguise often and at great distance, the way we are or would want to be.” ****

My collection of short stories includes three memoir pieces I don’t identify and I will use them here to explain why I argue that the fiction is more powerful, more truthful, if you will, than the so-called true story.

First, I give as example a comparison of what is essentially the same story told in fiction and also in memoir.

I put aside my novel Who by Fire (reviewed by Michael Johnson, regular columnist on FactsandArts.com) that was close to finished when my husband said after 22 years of marriage, oh-so-Greta-Garbo, “I need to live alone.”

This event stopped me in my tracks—and eventually I blogged my life while I was living it. That blog turned into the memoir (Re)Making Love. That book like Who by Fire is a love story but oddly one that fiction would probably not find credible.

I learned through these two books that the fictional account of my story has greater emotional truth and intellectual significance than the factual one that you can find online and in the 2011 Valentine’s Day issue of Real Simple Magazine where my husband and I tell our story.

Here’s how I learned what the so-called true story didn’t reveal. I am the reader for the audible.com version of Who by Fire. While reading it aloud in an NPR recording studio, I discovered my own book as if for the first time. I realized I’d written this novel to find the man I must have known on the unconscious level I was losing. Good fiction, meaning you know while you’re reading that the writer is risking her life, can go to this place of hard truth in a way that memoir because of its hold on the so-called facts can’t do if the writer is honest—and honesty is the key word here to understand my meaning.

Art and Fear by David Bayles and Ted Orland

In their book Art and Fear, David Bayles and Ted Orland explain our resistance to fiction—or to any art—this way: “[T]he prevailing premise remains that art is clearly the province of the genius (or, on occasion, madness). … [A]rt itself becomes a strange object—something to be pointed to and poked at from a safe analytical distance. To the critic, art is a noun.

“Clearly, something’s getting lost in the translation here. What gets lost, quite specifically, is the very thing artists spend the better part of their lives doing: namely, learning to make work that matters to them. … [W]hat we really gain from the artmaking of others is courage-by-association. Depth of contact grows as fears are shared—and thereby disarmed—and this comes from embracing art as process, and artists as kindred spirits. To the artist, art is a verb.” *****

I decided to further prove the force of fiction by revising the title character’s name to Olivia in each of The Woman Who Never Cooked’s stories. The allusion is to that character in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, the comedy that takes center stage in the story “Madness and Folly” about my father after he broke his hip—in real life and here in fiction.******

I could say that I am hidden inside the fiction—but in fact I am not. In the fiction, I used food and adultery as metaphor for the grief I bore through my mother’s, my father’s and my sister’s illnesses and deaths. I wasn’t sure who I was. As a prime example, I didn’t know when I wrote “The Woman Who Never Cooked,” the title story, that I would become that woman.

When I first wrote each of the stories the central character had the same name in every story because I knew that what I was doing was direct, tough purposefully artful exaggeration of my autobiography. My agent at the time suggested that I change the main character’s name to hide that fact. But the book only achieved publication after I added two of the three memoir pieces that had been published in literary magazines. All the stories have been published first that way, and the importance of the small literary magazine, I talk about here. You may go there and read that essay, entitled “Miss Rich is married and living in Cambridge, Mass.”, referring to the poet Adrienne Rich in an early bio when she first published, and the essay names places you might also choose to publish your work.

The stories in the collection that are memoir are: “Rugalach,” a tribute to my mother; “Losing,” a tribute to my father; and the eponymous closing story “The Woman Who Never Cooked.”

Let’s talk about the fiction and why I am now convinced that each of the other eight stories is more powerful, more truthful than the memoir—with the exception of “The Woman Who Never Cooked.” I say this about the last because it is written in third person like a fairy tale. The opening line is, “There once was a woman with 327 cookbooks who never cooked.” Through food, this true-to-its-core memoir tells the story of my mother’s, my father’s and my sister’s illnesses and the effect on living that their trials had on me.

For the second edition, I changed the central character in all the stories to “Olivia.” You may read one of the short stories “The Burglar” for free here at The Santa Fe Writers Project where the collection won the grand prize. That story and was published twice before appearing in the book of short stories. I’ll use this story to explain.

The image above that I use on my website was designed by Zaara.com and uses the line “What would the burglar advise?” a line inside the story—not exactly a line you’d expect in a story written as non-fiction.

The image above that I use on my website was designed by Zaara.com and uses the line “What would the burglar advise?” a line inside the story—not exactly a line you’d expect in a story written as non-fiction.

You would think me mad if I’d written this as memoir because the actual burglar is alive and well in this story—something only fiction can achieve without madness. Even Robin Hood and maid Marian appear in the story in an Internet game.

Audrey Hepburn as Maid Marian and Sean Connery in the 1976 flick.

Audrey Hepburn as Maid Marian and Sean Connery in the 1976 flick.

But the burglar himself is essential to express the love letter to my husband that I wrote here in the aftermath of my mother’s death and a burglary that actually did occur in our home while we were away visiting both our children at college. These facts I compress into the story’s essence.

So where is the truth? Does Ruth/Olivia actually desire the burglar? Does a burglar come to her home from his on Virgilia, a street near mine where the burglary actually occurred? Does it matter that I still own the locket that is in the burglar’s pocket and that the actual burglar chose all my other jewelry to steal and left behind the locket with its crude seal?

With that fact, the story wrote itself. Locket in hand that my mother had saved with a lock of her mother’s hair sealed inside, I went on the journey of discovery and the result is heartfelt non-fiction that cannot accurately be called that.

Joyce Carol Oates has put the conundrum of literary fiction so often spurned for the “true” story because, What can one learn from a “fiction”? this way:

“So much of literature springs from a wish to assuage homesickness, a desire to commemorate places, people, childhoods, family and tribal rituals, ways of life—surely the primary inspiration of all: the wish, in some artists clearly the necessity, to capture in the quasi permanence of art that which is perishable in life. Though the great modernists—Joyce, Proust, Yeats, Lawrence, Woolf, Faulkner—were revolutionaries in technique, their subjects were intimately bound up with their own lives and their own regions; the modernist is one who is likely to use his intimate life as material for his art, shaping the ordinary into the extraordinary.” *******

What I hope to have done here and for all the stories I’ve written that are quote fiction is to lift the curtain on that much misunderstood word. I argue that to dismiss out of hand the truth that close-to-the-bone, self revelatory fiction reveals is to miss a connection that may reveal to you those quote truths that would otherwise remain unspoken. The reason? Fiction, like all the arts that reveal through artifice, frees the unsayable. Why oh why would any of us who read or go to movies or art museums or photographic exhibits wish to miss that unsayable truth because we want the quote true story?

· *Dangerous Love my novel (am completing now).

· ** As an example, Leigh Gilmore, author of The Limits of Autobiography, notes that “…[T]he number of new English language volumes categorized as ‘autobiography or memoir’ roughly tripled from the 1940s to the 1990s. (Analysis based on data from the Worldcat database). See p. 1, footnote 1 of her book, Cornell University Press, 2001.

· *** David Shields, Reality Hunger, “412’ John Berger, p. 139; ‘421,’ David Foster Wallace, p. 141, Alfred A. Knopf, 2010.

· **** Lee K. Abbott, “Fifty Years of Puerto Del Sol,” Puerto Del Sol, Vol, 50, 2015, p. 194.

· ***** David Bayles and Ted Orland, Art and Fear, Capra Press 1997 p. 89.

· ****** Mary L. Tabor, The Woman Who Never Cooked, Mid-list Press, 2006. Mary L. Tabor, The Woman Who Never Cooked, second edition kindle and paperback version, Outer Banks Publishing Group, 2019.

· ******* “Inspiration and Obsession in Life and Literature,” Joyce Carol Oates, New York Review of Books, August 13, 2015.

Outer Banks Publishing Group author Mary L. Tabor contributed her writing expertise on Day 3 of a 30-day writing challenge sponsored by Wattpad.

Watch her video on creating the right point of view

Learn more with Mary’s bestselling stories about women’s challenges in today’s hyperspeed society, The Woman Who Never Cooked. The book is now published in its second edition by Outer Banks Publishing Group and available in our bookstore, on Amazon and in bookstores everywhere. The book is

“The American adult woman is featured in this debut collection of stories about love, adultery, marriage, passion, death, and family. There is a subtle humor here, and an innate wisdom about everyday life as women find solace in cooking, work, and chores. Tabor reveals the thoughts of her working professional women who stream into Washington, D.C., from the outer suburbs, the men they date or marry, and the attractive if harried commuters they meet.

“Her collection of short stories The Woman Who Never Cooked, published when she was 60, won the Mid-List Press First Series Award.

“Mary Tabor writes with astonishing grace, endless passion, and subtle humor,” wrote reviewer Melanie Rae Thon.

https://www.outerbankspublishing.com/writing/novel-writing-is-like-taking-a-good-photograph/

WHEREVER THE TIDE OF LIFE TAKES YOU AND YOUR LOVED ONES

The Origin of New Year’s Day

From the History Channel

The first New Year’s Day was celebrated on January 1 in the year 45 B.C. for the first time in history as the Julian calendar took effect.

Soon after becoming Roman dictator, Julius Caesar decided that the traditional Roman calendar was in dire need of reform.

Introduced around the seventh century B.C., the Roman calendar attempted to follow the lunar cycle but frequently fell out of phase with the seasons and had to be corrected. In addition, the pontifices, the Roman body charged with overseeing the calendar, often abused its authority by adding days to extend political terms or interfere with elections.

In designing his new calendar, Caesar enlisted the aid of Sosigenes, an Alexandrian astronomer, who advised him to do away with the lunar cycle entirely and follow the solar year, as did the Egyptians.

The year was calculated to be 365 and 1/4 days, and Caesar added 67 days to 45 B.C., making 46 B.C. begin on January 1, rather than in March. He also decreed that every four years a day be added to February, thus theoretically keeping his calendar from falling out of step.

Shortly before his assassination in 44 B.C., he changed the name of the month Quintilis to Julius (July) after himself. Later, the month of Sextilis was renamed Augustus (August) after his successor.

Celebration of New Year’s Day in January fell out of practice during the Middle Ages, and even those who strictly adhered to the Julian calendar did not observe the New Year exactly on January 1. The reason for the latter was that Caesar and Sosigenes failed to calculate the correct value for the solar year as 365.242199 days, not 365.25 days. Thus, an 11-minute-a-year error added seven days by the year 1000, and 10 days by the mid-15th century.

The Roman church became aware of this problem, and in the 1570s Pope Gregory XIII commissioned Jesuit astronomer Christopher Clavius to come up with a new calendar. In 1582, the Gregorian calendar was implemented, omitting 10 days for that year and establishing the new rule that only one of every four centennial years should be a leap year. Since then, people around the world have gathered en masse on January 1 to celebrate the precise arrival of the New Year.

By Anthony S. Policastro, Publisher

While we can now communicate in the fastest, easiest and most convenient ways possible using a myriad of devices anywhere, anytime to anyone in any corner of the connected world, I believe we are losing our ability to communicate.

Because communication is now ubiquitous, convenient, easy and instant, we have taken our writing skills for granted. Take emails. I believe that most of us are so comfortable with communicating with this medium that we use it like we are conversing with a good friend. Facebook and Twitter reinforce this mindset because we know our posts and tweets are reaching friends and relatives.

Jeff Bezos

The result is a quantum disconnect fueled by snippets of information that are most times incomprehensible.

When you a sitting face to face and having a conversation, the context of what you are talking about is always top of mind. But when you converse in the same manner with email the recipient may not read email for hours or days. The context gets lost. Complicate that with several acronyms in the copy and you might as well call a cryptologist.

We tend to write emails as if the recipient is sitting across from us leaving out the content because we believe the recipient will know what we are writing about. We have become lazy writers.

And I’m not alone in my view.

Walter Chen in his blog, IDoneThis.com, wrote about Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon who values writing over talking to such an extreme that in Amazon senior executive meetings, “before any conversation or discussion begins, everyone sits for 30 minutes in total silence, carefully reading six-page printed memos.”

Writing out full sentences enforces clear thinking, but more than that, it’s a compelling method to drive memo authors to write in a narrative structure that reinforces a distinctly Amazon way of thinking—its obsession with the customer. In every memo that could potentially address any issue in the company, the memo author must answer the question: “What’s in it for the customer, the company, and how does the answer to the question enable innovation on behalf of the customer?”

Like Bezos, Andy Grove of Intel finds value in the process of writing, but he doesn’t consider reading important. Grove considers the process to force

yourself “to be more precise than [you] might be verbally”, creating “an archive of data” that can “help to validate ad hoc inputs” and to reflect with precision on your thought and approach.

Writing, according to Grove, is a “safety-net” for your thought process that you should always be doing to “catch … anything you may have missed.”

So what is the solution? Write more, write casually, but include all the pertinent facts and pretend your reader knows practically nothing about what you are writing about.

By Anthony S. Policastro, Publisher When writing a novel it is a bit like taking that award-winning photograph. Don’t worry, you don’t have to take great photographs to be a great novelist.

In today’s world with dozens of media channels bombarding us every minute of the day, your book has to stand out from all the noise.

Here are elements that should be included in your novel and help to make your book stand out. You can pick and choose a few or include all, but you should have at least one.

Now here is how writing is like photography. Look at the photo below. Pretend it’s your realty – what you perceive through your senses. Now write a story about that photograph. You would describe the scenery, the asphalt path, the fallen leaves and twigs…overall what you wrote is pretty boring and a nondescript story unless those elements play a part in your plot.

Neuse River Greenway trail, Raleigh, NC

If you look closely or view the scene from a different angle or perspective there is a better story there.  The story reveals itself upon a closer look – a nice person found the pink sunglasses on the trail and was considerate enough to place them on the milepost, hoping the person would pass this way again and find the sunglasses. Out of the reality emerges a story.

The story reveals itself upon a closer look – a nice person found the pink sunglasses on the trail and was considerate enough to place them on the milepost, hoping the person would pass this way again and find the sunglasses. Out of the reality emerges a story.  The photographer views and analyzes the light, shadows, colors, shapes and how they play against each other and then picks an angle or position for the shot. Writing is the same. A good book is like taking a snapshot of reality, analyzing that realty, digging deeper until the hidden story is found in plain sight and then putting it to words. Tell us what you think. We would love to hear your thoughts.

The photographer views and analyzes the light, shadows, colors, shapes and how they play against each other and then picks an angle or position for the shot. Writing is the same. A good book is like taking a snapshot of reality, analyzing that realty, digging deeper until the hidden story is found in plain sight and then putting it to words. Tell us what you think. We would love to hear your thoughts.

Did you know Halloween’s origins date back to the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain (pronounced sow-in). The Celts, who lived 2,000 years ago in the area that is now Ireland, the United Kingdom and northern France, celebrated their new year on November 1.

This day marked the end of summer and the harvest and the beginning of the dark, cold winter, a time of year that was often associated with human death. Celts believed that on the night before the new year, the boundary between the worlds of the living and the dead became blurred. On the night of October 31 they celebrated Samhain, when it was believed that the ghosts of the dead returned to earth.

In addition to causing trouble and damaging crops, Celts thought that the presence of the otherworldly spirits made it easier for the Druids, or Celtic priests, to make predictions about the future. For a people entirely dependent on the volatile natural world, these prophecies were an important source of comfort and direction during the long, dark winter.

In addition to causing trouble and damaging crops, Celts thought that the presence of the otherworldly spirits made it easier for the Druids, or Celtic priests, to make predictions about the future. For a people entirely dependent on the volatile natural world, these prophecies were an important source of comfort and direction during the long, dark winter.

To commemorate the event, Druids built huge sacred bonfires, where the people gathered to burn crops and animals as sacrifices to the Celtic deities. During the celebration, the Celts wore costumes, typically consisting of animal heads and skins to ward off ghosts.

In the eighth century, Pope Gregory III designated November 1 as a time to honor all saints; soon, All Saints Day incorporated some of the traditions of Samhain. The evening before was known as All Hallows Eve, and later Halloween. Over time, Halloween evolved into a day of activities like trick-or-treating, carving jack-o-lanterns, festive gatherings, donning costumes and eating sweet treats.

Reviewed by Steven Felicelli

According to Ron Rhody’s wife, he is not eligible for authoring a memoir. He hasn’t won an Oscar or an MVP or a Nobel prize. And yet Rhody has a story he wants, needs, to tell. His story. And so that’s how he will tell it to us: as one of Our Own Little Fictions.

Reminiscent of Sarah Polley’s documentary Stories We Tell, Rhody meanders through his memory and down the real roads he’s traveled all over the U.S., from his beloved Frankfort, Kentucky, to California and back (via Florida and Alabama) and then back out to California. Along this circuitous route through his youth, manhood, and ancestry, we encounter all sorts of colorful characters, historical events, family triumphs, and tragedies, which in large part amount to the man whose story we’re being told.

The place closest to Rhody’s heart is clearly Frankfort, Kentucky. It is there his father, a newspaperman, fought for civil rights and to put down roots for his forward-thinking family. Though a wanderlust would uproot the Rhodys and send them all over the U.S., Kentucky kept calling them back to the heart of the heart of their country. In Our Own Little Fictions, Frankfort is origin and refuge, and it serves as the Ithaca of the author’s Odyssey.These chronicles of Rhody contain all the joy and pain of an American life that spans the Cold War to the present.

We meet his parents, grandparents, wife and children, friends and mentors. From animated anecdotes of a hard-nosed football coach doling out life lessons to the memorial for a dear friend and author of “sixteen erudite books,” we witness a life pass in time-lapse frames of laconic, Hemingwayesque prose.

Hemingway and his suicide haunt the narrative beginning to end. On a road trip from California to Kentucky, Rhody and his son make a scheduled detour to Hemingway’s home in Idaho (where he’d put the shotgun in his mouth).

”It seemed wrong that Hemingway had killed himself. Nature should have gotten him. Or chance.”

Later in the narrative and earlier in time, news of Hemingway’s suicide reaches Rhody, and he reflects on the premature tragedy, as well as his own (missed?) calling. These two time periods intermingle, and Rhody leaves Idaho with “an answer to a question I hadn’t known I’d asked.” Authorship was an alternative path he’d bypassed only to embark upon late in life.

Later in the narrative and earlier in time, news of Hemingway’s suicide reaches Rhody, and he reflects on the premature tragedy, as well as his own (missed?) calling. These two time periods intermingle, and Rhody leaves Idaho with “an answer to a question I hadn’t known I’d asked.” Authorship was an alternative path he’d bypassed only to embark upon late in life.

Late in life, indeed. The long road approaches its end and the loss of loved ones is an inevitability. Each story has the same conclusion, alas, and many of the characters we encounter in this Appalachian saga pass on in heartrending deathbed scenes and austere funerals. The depiction of these tragedies is sentimental, even cliched, but anything less/more would not be true to life. It is the commonality of these cliches that arise in endless variations, like updates of Shakespeare.

No, Ron Rhody is no Prince Hamlet, nor was he meant to be, but his story of “becoming,” with its conduplicatio, terse punch-lines, and homespun wisdom, is one that will always be in need of telling and retelling.

The feature photo above from left, Ron Rhody’s sister, Ann, his mother and sister, Mary Lou.