When I first met Alice Joyner Irby, I knew she had an extraordinary story to tell about her life, her family and people who crossed her path.

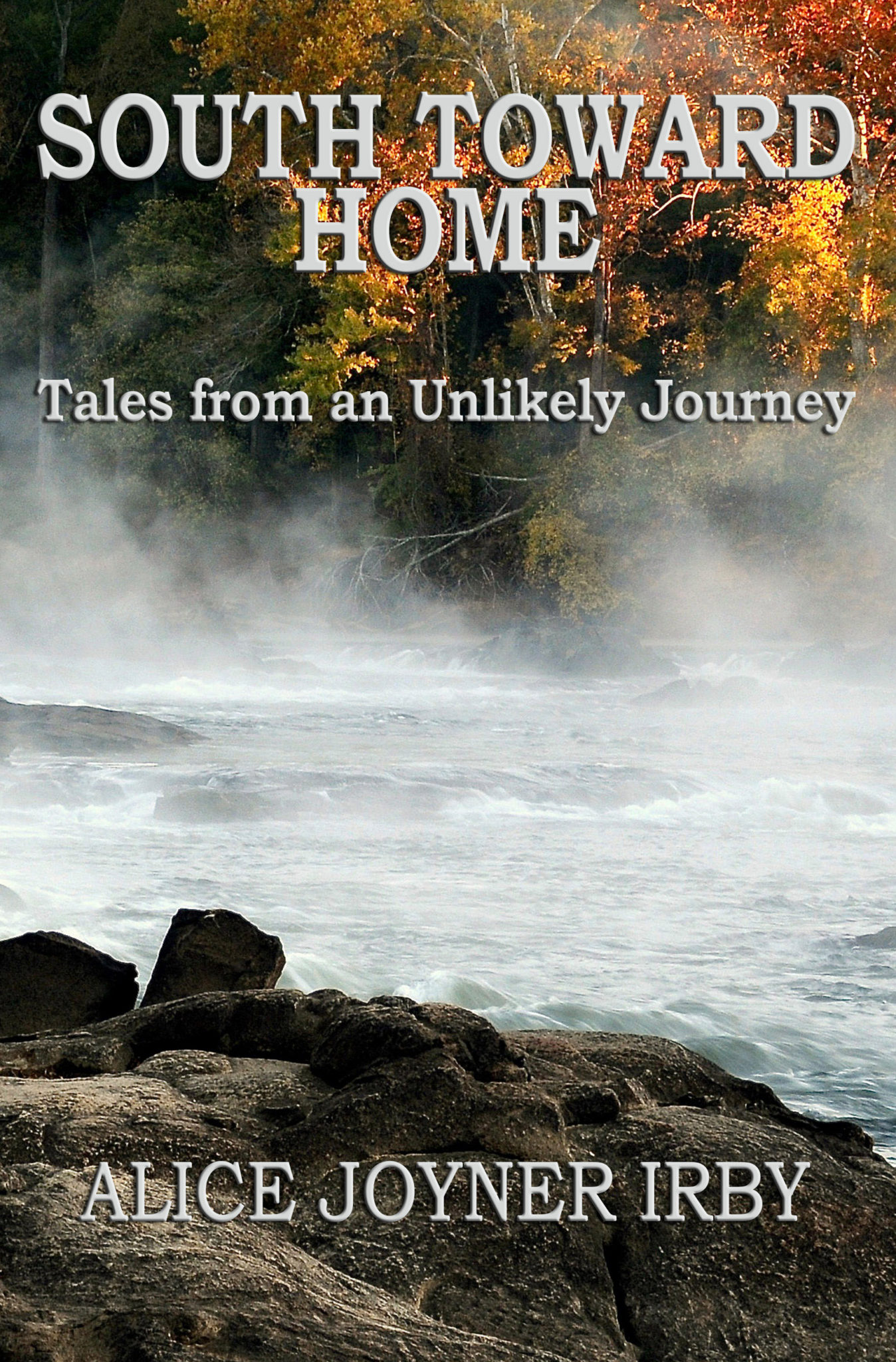

As she finished each chapter over a little less than year, I knew her extraordinary book was being created. And now it is here as South Toward Home, available on Amazon and in fine bookstores everywhere.

The Not-So-Friendly Skies is one of 26 stories in the book where Alice shows her grit in her struggle for women’s equal rights in a world dominated by men in the early 1960s.

By Alice Joyner Irby

MIXING IT UP

The Not-so-Friendly Skies

In the early 1960s B.C.—before cocaine, cohabitation, and the crises of riots and protests—it was business as usual for the airlines. At United Airlines (UA), that included Executive flights, code name for “men only.”

Two colleagues, Dick Watkins and Dick Burns—both heavy-set, tall men—and I were working together on a college grade-prediction study for Educational Testing Service (ETS), where I was then employed. The study included all four-year colleges in Indiana, 19 of them. Its purpose was to study the relationship among students’ high-school grades, SAT scores, and first-year grades in college.

Alice Joyner Irby in The Sacred Valley, Peru – 2018

Our fieldwork included visiting each college, explaining the project to participating administrators, and collecting data on freshman classes for analysis back in Princeton at ETS. Over a period of three years, the three of us regularly flew together to Chicago and then to various cities in Indiana.

At least it started out that way. Then, one day, the two Dicks were booked on a flight different than the one on which I was ticketed. Pleased that she was able to offer an upgrade, the travel agent arranged for them to go on something called an Executive flight. I did not qualify and instead had to go on an earlier flight and wait for my colleagues in O’Hare Airport so that the three of us could take a puddle-jumper down to an Indiana city.

“This won’t do,” I thought—even though the Women’s Lib movement was only a gleam in Betty Friedan’s eye and did not get into full swing until the early 1970s. And, it wasn’t until the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII, that federal legislation called for equal treatment in employment regardless of sex, race, color, religion, or national origin. Other legislation followed concerning housing, creditors and credit availability, and the well-known Title IX (1972). I was not an activist, but I expected to be treated fairly, and in this case, that meant being treated on a par with my peers.

For a while, I did nothing other than complain to myself and a few friends that every time I started out for Indiana, I got a little hot under the collar.

“Let’s see what we can do,” said Greg, a friend. At the time of our next scheduled trip, Greg and I decided to go to Newark airport to seek booking for me on the Executive flight scheduled to leave later that day. I already had a ticket on the earlier flight, knowing I would probably have to use it—but hoping an enlightened agent would rally to my cause.

“I am booked on Flight UA 323 to Chicago but want to change that to Flight UA 829 to be on the same plane as my colleagues.” I explained at the ticket counter. “My colleagues are Mr. Richard Watkins and Mr. Richard Burns,” I elaborated.

The United Airlines agent explained that the flight was not open to me.

“I know there are seats available, because I checked before I came,” I countered.

“It’s an Executive flight,” she stated.

“What does the term ‘executive’ mean? Is it a title?” Greg asked. “Or a level of education? Or size of desk or office? Or having supervisory authority? If so, Mrs. Irby has the same credentials as her two male colleagues.”

“What does the term ‘executive’ mean? Is it a title?” Greg asked. “Or a level of education? Or size of desk or office? Or having supervisory authority? If so, Mrs. Irby has the same credentials as her two male colleagues.”

The ticket agent paused, somewhat taken aback, then was clearly unable to give us a definition of “Executive.” She fumbled her words, saying something like, “The men on these flights have to work while in the air, and it is very distracting for women with small children to be on the same flight. They need quiet. You have a seat on the plane that is waiting to take off now…,” the agent attempted to explain.

“You mean Flight 829 is for men only? Is that right?” I asked with an edge in my voice.

When we didn’t leave and continued to press the issue, the agent excused herself and disappeared behind the partition at the back of the counter. A second agent came out, another woman, who reiterated the first agent’s words: “The flight is for executive men who need a quiet atmosphere when working, and United Airlines wants to make the flight as conducive to work as possible.” She could not tell us how she determined which men were executives who needed to work while in flight.

“Is every male passenger an executive? It seems that any male qualifies as an executive and no female does. Is that correct?” I asked.

Greg asked to see the written policy. Then, she, too, disappeared behind the partition.

We were left standing at the counter while other customers were being helped by an agent several feet away from us. A few minutes passed and a third agent, this time a man, came out and told me the written policy was at United headquarters in Chicago and I would have to inquire there for a copy.

“And, Madam, if you don’t go ahead and board the plane for which you are ticketed, the flight will leave without you. We have already held the plane 45 minutes for you,” the agent spoke in a sharp voice. Not taking that flight meant that I would not be able to meet my col-leagues in Chicago later in the day.

“Well, I have to get to Chicago, but I do intend to inquire about the policy when I get there. After all, I will have two hours to wait until my colleagues meet me,” I spoke just as sharply.

Dutifully, I walked to the gate with Greg by my side. The tactic of protesting “victimhood” was not yet in vogue until the twenty-first century. This was a new situation for me; I was not combative nor given to protesting, and I didn’t know quite how to proceed. Greg and I discussed what I would say to the attendants, if anything, as I walked up the steps of the plane to board. We decided I would stay mum except to greet them cordially.

In the 1960s, passengers boarded planes by departing the waiting room at the gate, going outside, walking to the parked plane, and then mounting steps attached to the side door of the plane. I gave Greg a hug, leaving him in the waiting room, turned around, and walked to the plane. At the bottom of the stairs, I put on my best smile.

I was the only person with a smile. At the top of the stairs, the pilot, the co-pilot, and the stewardess stood in the doorway, staring at me with scowls. No one said, “Welcome aboard.” Instead, the attendant said, “Mrs. Irby, your seat is 8B and you need to seat yourself promptly because we are running quite late.” Her harsh tone was not lost on me.

No one helped me to my seat. Passengers stared at me as if I were an angry or an uppity, trouble-making woman. Apparently, word had spread that I was holding up the plane. I did get my free Coke—but mine came with a splash and a snippy word from the stewardess. I was grateful that my seat partner did not scorn me—outwardly, anyway. He was quiet.

United Airlines headquarters was on the second level of the Chicago O’Hare Airport. After I disembarked, I found my way to the United office. Again I faced another counter with a partition behind it, a place to hide! A male clerk was standing there, idle and seemingly approachable.

“I understand that United Airlines has an Executive flight, and I am interested in knowing the provisions of that policy,” I said pleasantly.

Alice and her daughter, Andrea in Canada – 2015

Clerks there had been notified. They were ready. “I’m sorry, Ma’am,” answered the agent on duty. “It is filed away in another building. We will be glad to send it to you.”

Even though they had my name and could look up my address, I wrote down my name and address and handed it to the clerk. Most likely, that little piece of paper found its way directly into the trash can. I was not naïve enough to expect to receive the policy, which, of course, never showed up in my mailbox.

“What was so special about the Executive flight?” I inquired of my colleagues when we met in the O’Hare terminal.

“Oh,” Dick Watkins said, “its purpose is just to pamper men. Passengers are given socks to use if they take their shoes off, and pillows, free drinks, and snacks to go along with their cigarettes.”

“Nothing special,” Dick Burns chimed in. “United thinks that paying attention to men gives them a competitive advantage. And, as you know, most business travelers are men.”

Dick W and Dick B were not impressed with the perks and agreed with me that Executive flights did not make sense, especially since they were clearly discriminatory. Both of my colleagues were tall, large men and would have preferred more seat and leg room rather than the pampering.

What went unsaid was that the flight attendants, by United policy, were single women, very attractive and practiced in providing good service. I’m sure they were not flirts. Neither were the men, but doesn’t anyone like to be pampered?

Discrimination thrived inside the airline companies as well as in policies affecting their passengers: no men or married women were hired by the major airlines in that decade to serve as flight attendants. If a woman married, she had to resign her position.

I put the matter out of my mind and continued my work on the project with the two Dicks. Later that year, as I prepared to go to Washington to join the Johnson Administration for a year, the situation popped back into my awareness. I felt a twinge of resentment. Executive flights were not only discriminatory on their face but affected business arrangements and relationships as well. I deserved to be treated fairly, on a par with my colleagues. How could airlines get away with such policies? I was convinced they shouldn’t.

Maybe I was just sensitive to the winds of change as I prepared to go to Washington, on leave from ETS, to assist in establishing the Job Corps as part of President Johnson’s War on Poverty. Once there, I began working with a young lawyer, Stan Zimmerman, who was also on the Job Corps Director’s staff.

One afternoon, as we were idly chatting, I told him about my experience with United’s Executive flight.

“Let’s have some fun,” he said, upon hearing my story. We determined that the Executive flights were still in use. Using his law firm’s letterhead, Stan wrote to United Airlines, representing me as his client and raising the question of the legality of their practice. He insisted the airline cease such discriminatory flights, pointing to the proposed civil-rights legislation that President Johnson initiated and was beginning to move through Congress. Quite likely, United’s practice was not yet illegal, but that did not stop Stan and me from rattling our sabers.

United Airlines acknowledged receipt of the letter but that was all: no admission of anything. That’s what we expected. Life went on and, in fact, became all-encompassing at Job Corps headquarters as we worked feverishly to develop the infrastructure of the program.

To our surprise and pleasure, a couple of months later we determined that, quietly, the UA “Executive flight” had taken a nose dive into the dust: no widely distributed press announcement, not even a newspaper article. Nary a murmur from a traveling businessman that elimination of the Executive flight reduced his productivity—remember, they were supposed to be segregated from women so they could work!

The flight merely disappeared from the list of arrivals and departures at airports and was no longer listed in the airline guide used by travel agents.

After work that day, Stan and I raised our glasses with a toast: “A Hand Up for Women’s Rights, and a new nail in the coffin of Inequality!”

About the same time, another woman from Weldon High School stuck her neck out. Jean Satterthwaite moved to New York City after graduation from the Woman’s College, married a school counselor/writer and, when looking for work, realized that The New York Times’ classified employment ads were divided according to MEN and WOMEN. In other words, not only was employment policy discriminatory in many places, job descriptions and classifications were as well.

Occasionally, the policy disadvantaged men, as in the case of UA’s policy on flight attendants needing to be women, but, by far, its sword fell most punitively on opportunities and prospects for women. Jean and a few other women organized a protest of The Times’ classification system by gender, which had been copied, quite naturally, by every other major paper in the country. They wrote letters, made telephone calls, and brought the policy to the attention of civic clubs and business associations, urging them to write and call as well.

The women were successful. After some foot-dragging and flimsy excuses, The Times backed down, realizing it lacked a defensible business reason to continue the practice. Things changed—want ads were listed by job classification, not gender.

Eventually, other major newspapers followed its lead. Jean went on to be the first president of the NYC chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW).

Greg, who came to know both Jean and me, vowed there was something in the water we drank in Weldon or the food we ate in the dining halls of the Woman’s College. Where had the seeds of that independent, assertive, spunky spirit been planted?

Who knows?

Maybe the seeds were borne by the fast-flowing, powerful waters of the Roanoke River. Or by the toil of strong-willed, independent farmers and merchants, laboring without a government safety net to help them in hard times.

Maybe they were passed along in the discipline that Mr. Thomas, our school superintendent, enforced with his reliable sense of fair play.

Or maybe by the demeanor and actions of our role models, the women faculty at the Woman’s College, or the history and philosophy professors there who awakened dormant portions of our minds to show us new horizons. Or maybe the seeds germinated first in the rich black dirt of Eastern North Carolina that stuck to our feet and made us independent, adventurous Tar Heels.

September 2017